Liverpool has been planning ways to let traffic move more effectively around its central area for a long time. In fact, the very first plans for an inner ring road were drawn up in 1853. In the 1920s and 30s, John Brodie, the designer of Liverpool's many miles of suburban dual carriageways, campaigned for an inner ring road to complement Queens Drive. And of course, in the 1960s, there was the Liverpool Inner Motorway plan.

The crucial document on the LIM is the unassumingly titled Shankland Report No. 7, which was published for the City Council in 1962. Its pages contained the final conclusions of an exhaustive study into the idea of building an inner ring road as part of plans to regenerate the city centre.

The Report

The consultants seem to have cast the net far and wide in searching for the best possible design. They established first what kind of road it had to be - deciding on a motorway on the basis that one lane of an urban motorway had the same traffic capacity as a four-lane surface street, and this was therefore the most cost- and space-effective option.

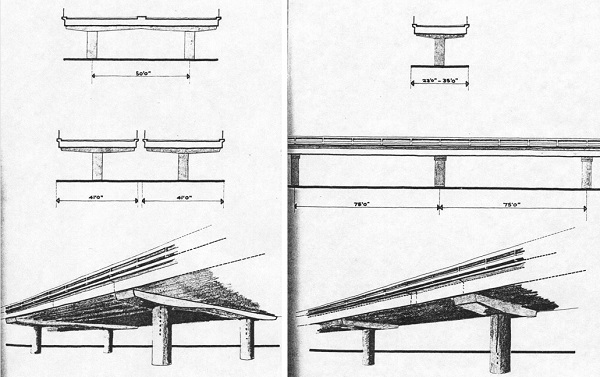

To build a motorway, the route could not remain at ground level. To achieve full grade-separation, and because of the challenges of sinking the route below ground level, the entire road was to be elevated. It was recommended that much of the land underneath could be made available for service industries or other purposes - one architect's sketch showed the LIM running on the roof of a shopping centre - and in some places, buildings could be constructed over and under the road (imagine a building with a hole in the middle, through which the motorway passes). The details of a suitable design to elevate a motorway without being too obtrusive was solved by designing the support piers at this early stage.

The consultants considered tidal flow on the motorway, and while they decided its benefits would be minimal on a ring road where peak hour flows would not be more heavy in one direction than the other, it should be seriously considered on improved radials. Even right-hand driving was taken into consideration, and the final design was apparently drafted with the possibility of a change to right hand driving in mind.

Each section of the LIM was to be built before any of the radials it connected to, in order to .avoid the imposition of intolerable traffic congestion at the centre of the city". The report recommended that the whole route should be complete by 1975, and highlighted which sections should be prioritised.

The cost in 1962 was estimated at £23m - a bargain by today's standards - of which £8.5m was the cost of buying up land not already owned by the council. This did not include estimates for the amount of money that could be made selling or renting the land underneath the LIM once it had been built.

Lastly, the report gave the specifications for the motorway as follows:

| Max. mainline design speed | 50 mph |

| Min. mainline design speed | 20 mph |

| Max. sliproad design speed | 30 mph |

| Min. mainline curve radius | 750 ft |

| Min. sliproad curve radius | 300 ft |

| Min. curve radius of other roads | 150 ft |

| Standard lane width | 12 ft |

In addition, full hard shoulders were to be provided on the mainline, and were recommended on sliproads.

The Route

The route itself is surprising in a number of respects - but most importantly in that the LIM was not intended to function as an inner ring road. The southernmost junction, the St James Interchange, does not cater for movements around the city centre. In addition, the section of motorway along the waterfront has no access points whatsoever.

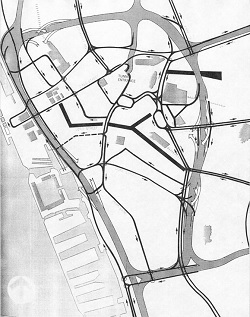

A second report, Shankland Report No. 11, is concerned with car parking in the city*. It shows intended locations for development of inner city car parking facilities, details access points from the LIM, and also shows a diagram with what appears to be an alternative layout. This layout does not appear in the first report, even though both were published in 1962. It shows a southern section of the LIM, separating the St James Interchange into two three-way junctions. However, this simply shows the land area for the motorway and not the revised layout. Most importantly, this report reveals that the LIM was intended to have free-flowing sliproads into multi-storey car parks at a number of (undisclosed) locations.

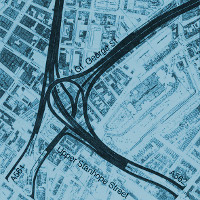

Nonetheless, the original route as described by the Shankland Report No. 7 was diagrammed in great detail, including the elevation and gradients of all the sliproads and carriageways. The plans for each section are shown below. Because the maps they were superimposed onto** were faint, they have not copied well, so there are labels highlighting principal streets and landmarks to aid orientation. The plans work clockwise from the north-western corner.

Following the route on a modern OS map will reveal how much land reserved for the LIM is now taken up by large signalised junctions.

The north-west corner has a three-level interchange that gives priority to the waterfront route, which becomes a northern radial motorway at this point. Access is available between surface streets and the north and east arms. To the east the LIM follows Leeds Street, now dualled on what was presumably land reserved for the motorway.

An extremely short motorway journey is possible from Great Howard Street to Vauxhall Road here, perhaps to do with the fact that Exchange Station was planned to become a large car park at the time.

Travelling clockwise around the circuit, a short weaving section takes the LIM to the junction with Byrom Street. There is now a large flat junction on this site. The interchange is on four levels, connecting to the Queensway Tunnel to the south. It is interesting that Byrom Street is not upgraded to motorway through the junction - it is not clear whether is was to be upgraded or not. The next junction is the Islington Radial - M62 by any other name.

The through route at Byrom Street becomes the off-slips to the M62 here, which seems sensible given the likely traffic movements here. Behind Lime Street Station, there is a bizarre level junction with only three movements provided.

The next section has a south-facing junction with Mount Pleasant, then an unusual connection with Duke Street. A three-level junction carries two sliproads under the LIM, which then loop around 270 degrees, presumably to arrive at ground level on this steeply sloped site. The unshaded sliproads here indicate that this was to be part of a separate project, perhaps as part of other upgrades to Duke Street or Berry Street.

Following Great George Street, the LIM has a short weaving section from the Duke Street junction, then reaches the St James Interchange, perhaps the centrepiece of the whole project. Built on at least three levels, it connects both south-facing arms of the LIM to two radials - one heading south, one east - and both radials to each other. But importantly, it does not connect the two parts of the LIM together.

Both radials are both shown here with frighteningly short weaving sections before their first junctions. Both are only projected beyond that point. To the north of the interchange, the waterfront section of the LIM is built literally on top of Park Lane.

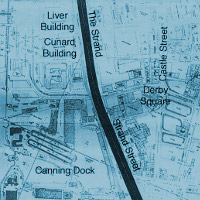

The final part is the waterfront section of the LIM, and is literally featureless, following Park Lane, then Strand Street to pass the Albert and Canning Docks. The elevation plans reveal that it drops to ground level as it travels along The Strand, perhaps in reverence to the Royal Liver and Cunard Buildings. The Strand is an enormously wide street here and could easily accommodate several lanes each way with the LIM in its central reservation. Towards Princes Dock, the route widens out again to meet the interchange in the north-western corner.

The LIM Cancelled

The Shankland Report's central recommendation to the City Council was that it submit the plans to the Ministry of Transport immediately to secure funding so that work could start as soon as possible. It is easy to imagine that the Council then spent a year or two contemplating the idea rather than jumping into action.

One of the points made in the report is that no one part of the LIM could possibly function alone. While it ought to be constructed in phases, none of them would really work until the whole thing was built. If the City Council was at all uncertain whether it would be able to build all the sections (a plan involving some 13 years' commitment) then it would most likely not clear construction of the first phase because of this.

Why would it not be certain that it could build the entire route though? The report, near the beginning, describes the three central assumptions that were made throughout the study. They were as follows:

- That the central area of Liverpool will continue as a significant commercial regional hub.

- That Liverpool will continue as a major port.

- That the central area will continue to be the largest single centre of employment in the region.

Arguably, two of those assumptions were safe to make. But in 1962 it would not yet have been clear that the ports of Liverpool were in for a rough time, and the economic decline that the city suffered for several decades afterwards almost certainly meant that ambitious plans like these were put on hold.

* The report on parking also, interestingly, decided that three minutes was the maximum acceptable walking distance from car to destination, and suggested this distance could be increased, so car parks could be placed further away, if the City Council provided shopping trolleys in its car parks.

** These maps appeared to be much older than the early 1960's. One sheet showed the Queensway Tunnel as the A57.