British planning is full of strange ideas, some of which have worked and some of which haven't. Probably the most ambitious motorway project was the London Ringways scheme, which unsurprisingly burned out very quickly. What is stranger, though, is that while the Ringways were still in planning, something even more extraordinary was being given serious consideration by the Government.

A sound principle

In 1966, an architect by the name of AE Matthews presented a paper to the International Road Conference in London. He started from a very sensible ideal: that most traffic in central London was either passing through or looking for somewhere to park, and that if you could find ways of letting it pass through or letting people park that involved the use of as little of the street network as possible, the city environment would be much more pleasant.

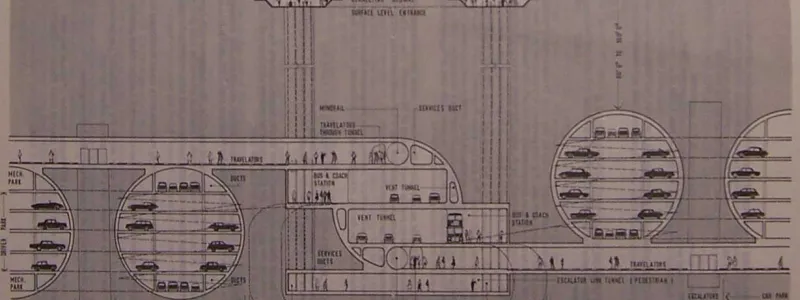

His curious answer to this requirement was to put the traffic underground somewhere, providing facilities for parking and through-traffic beneath the streets and out of the way. This underground infrastructure would allow traffic to enter and exit onto major radial routes outside the centre, but would have no access for traffic to come to the surface anywhere within the central area. Instead the underground car parks would be linked to the surface with pedestrian escalators and lifts.

Underways

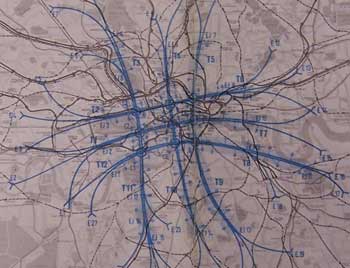

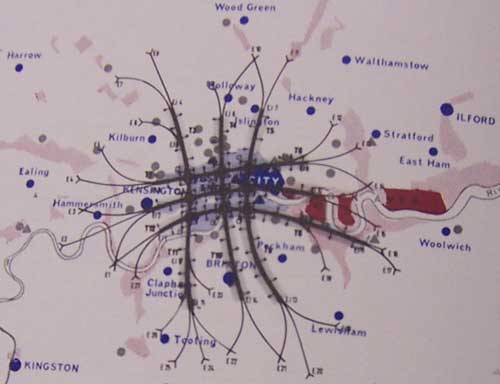

Matthews' proposal detailed every aspect of the Underways scheme. There were to be six tunnels in all, three running north-south and three east-west, with nine free-flowing underground junctions connecting them. At their ends they would split into two or three branches so that each major radial into London would have one or two direct accesses to the Underway network.

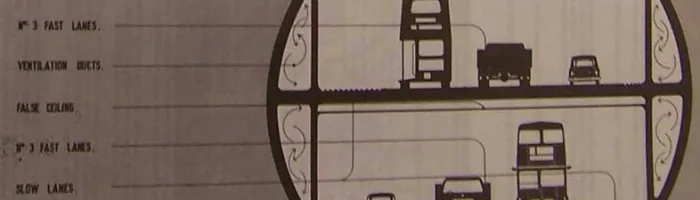

The routes were to take the form of single-bore tunnels, 60ft (18m) in diameter, containing a three lane motorway with full hard shoulder, a two-track monorail, pedestrian walkways and service ducts. They would run between 80ft (25m) and 160ft (50m) below surface level.

At frequent intervals, short lengths of parallel tunnel (of the same diameter) would house multi-storey car parks, bus stations and other facilities, with escalator and lift access to the surface.

A practical proposal

The Underways proposal came complete with a summary of its expected cost in comparison with the building of the surface Ringway network. It claimed an advantage in having no demolition costs and no extra expense or resources for the rebuilding of facilities that would have to be cleared for a surface motorway route. The tunnels were almost half within Ringway 1 and the rest well within the confines of Ringway 2.

At 1966 prices, Matthews considered Ringway 1 to cost £19.1m per mile, and a comparable surface motorway in the very heart of London (the City or Westminster for example) to cost up to £260m per mile. Averaging this to £140m for the whole area within Ringway 1, he calculated that building the Underways at ground level would cost £5.6bn - whereas it would be a bargain £530.4m in tunnels. To provide the same parking facilities - space for 100,000 cars - at ground level in four-storey buildings would take up 175 acres and cost £262.25m (not to mention involving the demolition of most of central London).

The final cost of the Underways was calculated at a confident £20m per mile: rather ambitious considering it involved 100 miles of tunnel that would be 18ft (5.5m) greater in diameter than any other tunnel in existence at the time. Matthews' final figure, including £200m for land costs for ventilation shafts and pedestrian accesses, came to £2.4bn. An extra sweetener was that these 100 miles - much of it for car parking - would all be at the same diameter, allowing economies of scale. Some would argue that if you're spending £2.4bn at 1966 prices, the word "economy" does not enter into it.

The Ministry investigates

It would be realistic to dismiss this as the daydreaming of an architect, drawing up plans for his own 1960s utopia. But alarmingly, it was given serious consideration by the Ministry of Transport in 1969. And worse yet, the explanatory note that the Ministry attached to the report when it was circulated to its senior engineers mentions that:

"Underways is an updated version of a paper originally presented at the Fifth World Meeting of the International Road Federation in 1966. This earlier paper was included as supporting evidence at the GLDP [Greater London Development Plan] Inquiry."

So not only did a few suits from the government have a look at the plans, but they were put forward as a serious part of the GLC's development plans which went to public inquiry. All quite incredible!

The first response comes from GS Rowland, an engineer who seems to have skimmed through the report without reading the detail. He complains that it won't work for the following reasons:

- "Need for frequent, large, expensive and possibly noisy ventilation shafts.

- "High cost of cleaning, lighting and maintenance.

- "Complexity of tunnel-to-surface junction arrangements. The surface areas required are likely to be greater than for conventional layouts. The varying tunnel cross-sections at interchanges would increase construction costs and slow down progress.

- "Possible sterilisation of surface development. Routes may have to avoid passing under tall buildings.

- "Surface routes can be built comparatively quickly in short stages and these can be brought into use as soon as completed. Tunnels will take much longer to build and would have to be built in long and expensive lengths."

A lot of this is true, but it misses the point that the tunnels will be up to 160ft below the surface - very deep boring that would not affect much on the surface - and would have no surface accesses once they got underground. Oops!

Mr Rowland also - more usefully - puts together his own cost estimates which takes into account tunnelling technology at the time and factors in the untested nature of such large tunnels, and puts them at £40-100m per mile - two to five times Matthews' estimates.

The Ministry's final summary stated that its own research indicated a cost above £4bn, which would be in addition to the surface Ringway network, and that it was investigating smaller scale tunnelling for urban motorways, suggesting that "it is not established that tunnels can often 'break even' at present" and that nothing like the required resources are available to pay for it all.

But the summary of the paper is very clear:

"While, therefore, a considerable amount of work on constructing motorways below the surface has been and is being done by the Department, this is not specifically related to Mr Matthew's [sic] 1966 paper. The Department's view is that this paper will not in fact repay further study or effort either generally or in its application to London."

...which pretty much says it all.

Sources

- The Underways are extensively documented, including the text of AE Matthews' report and the Ministry of Transport's investigations and response, in the National Archives file MT 106/427.

Picture credits

- Original images are extracted from file MT 106/427 at the National Archives under the Open Government Licence.