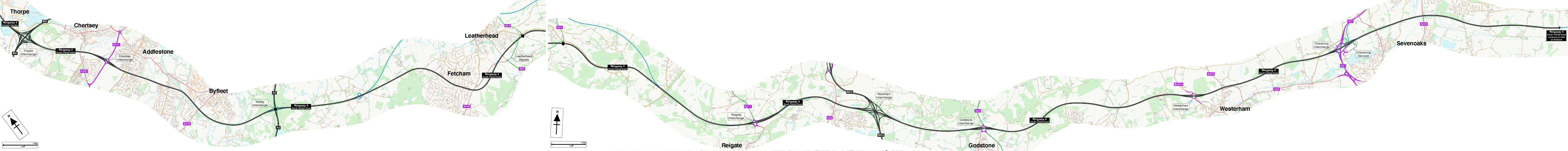

Rolling through Kent and Surrey, somewhere between the end of leafy London suburbia and the start of the North Downs, the South Orbital Road would carry long-distance traffic between the Channel ports and the west.

The number M25 originally belonged to the South Orbital. It was the motorway that would relieve the A25, an overloaded route from Kent through to Guildford. East-west journeys that had no business in London would speed across the south of England, far from the slow-moving city, surrounded by what planners hoped would be some of the finest scenery to grace the motorway network.

Whether you consider the M25 between Sevenoaks and Guildford to be fast and scenic, if you drive it today, is a matter of opinion, but it's easily the most rural stretch of the modern-day orbital motorway. It has the most widely spaced junctions and the least suburban surroundings. It's easily the closest match to the original vision for this road, which was a fast parkway where motorists could enjoy not just speedy journeys but also stimulating views of fine countryside.

That beautiful and efficient parkway was not, of course, supposed to have four lanes in each direction, a thundering concrete surface and a reputation for stop-start traffic jams all day long - but then that is the danger of building a road like the South Orbital. If you build it, it might turn out to be more useful than you expected.

Strictly speaking, the name "South Orbital Road" was used to refer to any part of Ringway 4 south of the Thames, but for the convenience of breaking the whole orbital into three manageable parts, this page refers only to the route between its terminus in Kent and the point where it meets the M3.

Outline itinerary

Continues from R4 Western Section

M3 (Thorpe Interchange)

A317/A320 St Peter's Way (Chertsey Interchange)

A3 (Wisley Interchange)

Local connections to Leatherhead

A217 Reigate Hill (Reigate Interchange)

M23 (Merstham Interchange)

A22 Godstone Hill (Godstone Interchange)

B2024 Croydon Road (Westerham Interchange)

A21 Sevenoaks Bypass (Chevening Interchange)

M20

Route description

This description begins at the eastern end of the route and travels west.

Wrotham to Reigate

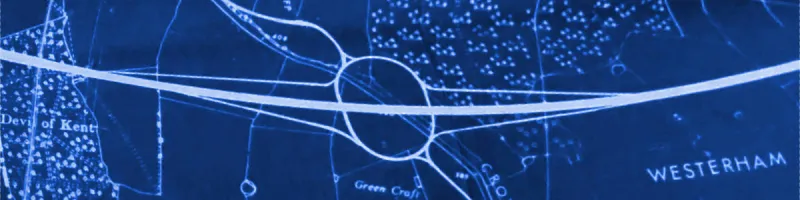

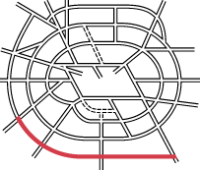

Branching off the M20 at Wrotham in Kent, the M25 South Orbital Road would travel west, skirting the northern edge of Sevenoaks, a route that was eventually built as the M26. At Chevening, a three-level stacked roundabout interchange would connect to the A21 Sevenoaks Bypass, and a motorway service area would also be sited here. Unlike the existing M25 junction 5, the junction would provide access in all directions.

The route then follows the line of the modern M25, with only minimal differences to the motorway that was eventually built. The most noticeable change is that an additional junction was proposed at Westerham, connecting to the B2024 Croydon Road; its layout suggests extra connections were possible leading south towards the A25 and east towards the A233.

Beyond Westerham, the motorway continues west, with another interchange for the A22 at Godstone (now M25 junction 6) and with the M23 at Merstham. It then climbs steeply to reach the A217 Brighton Road at the top of Reigate Hill. The distinctive westbound off-slip to this junction, which extends for more than a mile up the hill alongside the motorway, was added when the M25 was widened and is not part of the motorway's original design.

Reigate to Thorpe

Beyond Reigate, the South Orbital would continue along the modern M25 line until it passed under the B2032 Dorking Road, where it would turn west through Headley to approach Leatherhead from the south-east, closely shadowing the route of the B2033 Reigate Road.

The motorway would run parallel to the A24 Leatherhead Bypass before turning north to pass through Fetcham, using land reserved for the South Orbital since the 1930s. The corridor has since been built over, but modern housing estates Highfields and Bickney Way are easily identified on a map as occupying a thin strip of land through the middle of the village.

Turning west, the motorway would rejoin the modern M25 line at Downside, near modern-day Cobham Services, interchanging with the A3 at Wisley and following another protected corridor through Byfleet to reach a local junction near Chertsey, now M25 junction 11.

Continuing north, the motorway would reach a large free-flowing interchange with the M3 at Thorpe, built as planned in the mid-1970s and in service today as M25 junction 12. North of this point the remainder of the South Orbital Road is described as part of the Ringway 4 Western Section.

A flight of fancy

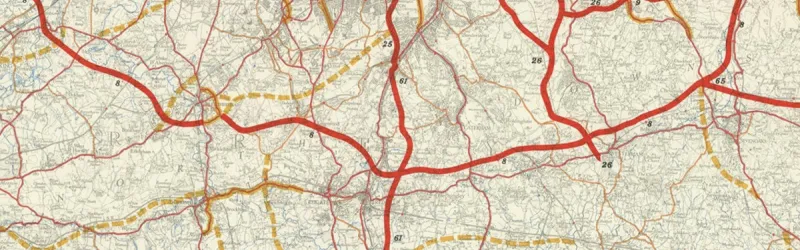

The South Orbital Road was first proposed in 1937 by Sir Charles Bressey, as part of his grand Highway Development Plan. Few of Bressey's ideas made it to the construction stage (at least, not in his lifetime, and not without passing through other hands first), but his plan was incredibly influential. Of all his projects, the South Orbital was one of the most enthusiastically pursued.

"The route as planned passes through some of the finest scenery in Kent and Surrey and the whole route should be treated as a parkway, with access restricted and "flyovers" provided at all major crossings."

Bressey understood the need for the South Orbital but he had trouble working out where it might go. Within London's built-up area, reasonably up-to-date mapping could be relied upon and the landscape was well enough documented that he could choose road alignments from the comfort of his office. Out in rural Kent and Surrey, however, the situation was very different.

Finding that mapping of the countryside beyond London's borders was decades out of date, and that the rural landscape was harder to judge from the printed page, Bressey tried something more ambitious. In August 1936, he chartered a plane from Imperial Airways and asked them to fly him back and forth between Maidstone and Staines.

Based on what he saw through his aviator goggles, Bressey plotted a line for the South Orbital that skirted the northern edges of Sevenoaks and Westerham, climbed the escarpment to Reigate, borrowed a length of the then-new Leatherhead Bypass and swept around Weybridge.

So successful was this aerial reconnaissance that his alignment went on to be protected from development by Kent and Surrey County Councils. In fact, remarkably, from Wrotham to Godstone the modern M25 never strays more than a couple of kilometres off Bressey's line, and the motorway is even more squarely within the corridor he identified between Fetcham and Staines. The only significant deviations are around Leatherhead and Reigate, where motorway standards called for smoother curves and gentler gradients.

It's strange - but absolutely true - that about a quarter of the modern M25 is effectively built on a route identified from a single aeroplane flight in the mid-1930s.

Grander plans

After the war, it was a while before Bressey's plans for a South Orbital Road were dusted off. Eventually, a combination of rising traffic to the Channel ports and congestion on the A25 caused the Ministry of Transport to examine the idea again.

The route had been protected in the Surrey and Kent County Development Plans, drawn up in the late 1950s, so with some refinement it was not difficult to site the road or begin design work. An initial length, between Reigate and Sevenoaks, was planned as an all-purpose road, intended to be an off-line bypass of the A25.

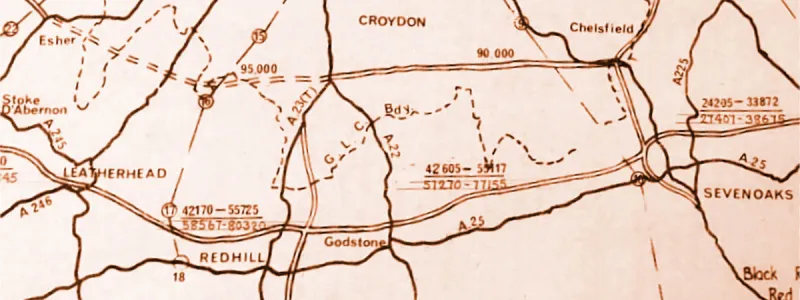

By 1965 it was becoming clear that the demand for this road - and the demand for road travel in the London area in general - was much greater than Sir Charles could ever have imagined. The Greater London Council were calling for a new motorway through the suburbs (then called the "D" Ring, but soon to be known as Ringway 3) and yet - even though it would only be a few miles away - the South Orbital was also going to need to be more than just an A25 bypass.

"It would be wrong to regard the 'D' Ring and the South Orbital as being alternatives or competitors. Both roads are justified but each would serve a different function. The amount of traffic which could be regarded as equally catered for by either is relatively small."

By the following year a decision had been taken to build the South Orbital as a three-lane motorway, and the transport minister Barbara Castle announced the change with a statement that said its purpose was to bypass the A25 and to serve traffic from the Channel ports heading for the west, "whether from a Channel Tunnel or existing ports". The new motorway would, naturally, be called the M25.

For and against

The South Orbital faced opposition, just like the rest of the Ringways - but it also had its supporters. Opinion was divided along county lines.

From the early 1960s, when the South Orbital Road became a serious prospect, residents of towns and villages in Surrey began to mount a campaign for its construction. The "A25 Villages Association" was formed to lobby Surrey County Council and the Ministry of Transport. Indeed, there survives a thick folder of correspondence from the mid-1960s about the South Orbital, half of which are letters on "A25 Villages Association" headed notepaper, and the other half of which are replies addressed to them.

The recurring theme of the correspondence - years of it, amounting to hundreds of letters - is that the people of Oxted, Godstone and Buckland wanted the South Orbital to be built far sooner than the Ministry could possibly promise, and ideally without any impact whatsoever on the delightful Surrey countryside. No reply from Whitehall, not even one written personally by Ernest Marples, could satisfy them that relief for the A25 was on the way soon enough.

A few miles to the east, the residents of Kent felt rather differently. Proposals for the new motorway met with opposition all along the line, and the Ministry spent no small amount of time negotiating trivial adjustments to keep landowners happy.

The residents of Westerham were so insistent that their village should have nothing to do with the road that they formed the "Westerham Interchange Resistance Group", actively (and successfully) campaigning for the interchange proposed near Westerham to be deleted from the plans.

When the Godstone-Sevenoaks section went to public inquiry in 1973, some of the inspector's private notes were accidentally circulated to objectors - a situation described by local press as a "bureaucratic fiasco" that caused the inquiry to be called off, the motorway proposals to be withdrawn entirely and the whole scheme to be delayed by a year or more. It was not clear why the documents were photocopied or distributed at all, or who was ultimately responsible - but the withdrawal of the scheme and the revision of its design were a cause of much celebration in the surrounding villages.

Closing the circle

In the end, the first bit of South Orbital to be built was between Reigate and Godstone. By the time it opened to traffic in 1976, the original South Orbital was already dead, replaced with plans to join up bits of Ringway 3 and Ringway 4 to make something called the London Outer Orbital Road - in other words, the modern M25. It wasn't long until the M25 number had been applied to the whole circuit and not, as originally intended, just the south and west sides.

Very little of the South Orbital motorway plans from the 1960s were changed when the LOOR lumbered into view, but one or two things did. One was the invention of the M26. As originally planned, the M25 would have continued east from Sevenoaks to meet the M20 Ditton Bypass near Wrotham. Now that the motorway would turn north to meet Ringway 3's Dartford crossing, the orphaned length was granted a new number, becoming the M26 Wrotham Spur.

Where the M25 and M26 meet at Chevening, planners had originally sketched a three-level stacked roundabout junction, but the re-run of the botched planning inquiry resulted in major changes, introducing the free-flowing interchange that exists today. It was created not to improve traffic flow but to move the bulk of the junction further away from Sevenoaks and Chipstead village - though in the end the new design was a stroke of luck because, without it, the M25 would today turn a corner by passing through a big roundabout.

The last of the major changes was that, in a public consultation exercise, the motorway was shifted from its course through Fetcham and south of Leatherhead to a new line around the north, creating a smoother motorway line and keeping it further from peaceful suburbia. It was the biggest amendment to Bressey's South Orbital plans, completing the project's long journey from pre-war parkway to modern orbital motorway.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Photograph of M25 near Godstone taken from an original by Robin Webster and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Plans of Westerham interchange, M25 at Wrotham and Chevening interchange extracted from MT 121/557.

- Photograph of M25 through Byfleet taken from an original by Alan Hunt and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Map of Bressey's route is from the Highway Development Survey (1937), now out of copyright, and hosted by SABRE Maps.

- Traffic forecast diagram extracted from MT 106/293.

- Photograph of A25 at Bletchingley taken from an original by Carl Ayling and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Merstham Interchange taken from an original by Peter Shimmon and used under this Creative Commons licence.

Sources

- Route, Wrotham-Leatherhead; M25 originally applied only to SOR; Westerham interchange layout; Chevening interchange layout and services: MT 121/557.

- Route, Leatherhead-Weybridge; change of course at Leatherhead: CC971/2/7/13 held at Surrey History Centre.

- Route, Weybridge-Thorpe; public inquiry controversy: MT 120/215.

- SOR proposed by Bressey; surveyed by plane: MT 39/360; Bressey, C. and Lutyens, E. (1938). Highway Development Survey 1937: Greater London. London: Ministry of Transport.

- Route appeared in KCC and SCC County Development Plans; SOR support in Surrey; opposition in Kent: MT 110/87; MT 110/88.

- Originally planned as all purpose; MOT memorandum justifying both R3 and SOR; Barbara Castle's announcement of SOR as M25: MT 110/110.

- Changes at Chevening to move interchange: MT 152/195.

- Creation of LOOR; adoption of M25 for whole circuit: MT 120/315.