If it were being built today, a 44ft (13m) diameter tunnel under a river estuary, with two branches, underwater junctions and four tunnel portals to be squeezed into city centre locations would be an incredibly large-scale project.

In 1923, the only viable prospect was to have it excavated by hand. No tunnel of comparable diameter had been built before, and nothing existed to match its length or its complexity. No ground surveys could be carried out. No mechanism existed by which central government could plan such large-scale schemes. The railways, which held enormous political sway, were vociferous opponents, given that they operated the only existing river crossing. The odds were, really, stacked against it.

All the same, the Mersey Tunnel Joint Committee was formed in 1923 and within a little more than two years work had started. When it opened, it was the engineering marvel of the world.

Schemes and squabbles

By the time any road crossing was planned, the Mersey had already been crossed once with the Mersey Tunnel, a railway tunnel opened in 1886. Most of the goods, vehicles and luggage from the busy ports were forced to cross by the various ferries and steamers — many owned by Liverpool and Birkenhead's Corporations — that did the short trip across the river.

By the 1920s cross-river traffic was increasing sharply. In 1922, 62,000,000 foot passengers made the trip, double the number twenty years previously. The vehicle figures made an even sharper leap, from 36,000 in 1901 to 640,000 in 1921. Something needed to be done, and the three options proposed were a bridge, a tunnel or an improved ferry service.

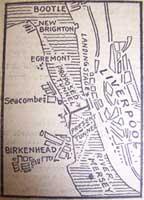

The bridge plan was short-lived. The suspension bridge (shown in blue on the map above) would have to be of a sufficient height to clear shipping and its main span would be more than 3,000ft (900m). When the proposal was publicised in September 1923, the tunnel was costed at £6,400,000 while the bridge was £10,550,000. The resulting working party was therefore named the Mersey Tunnel Joint Committee.

Initially the tunnel was to connect the ferry terminals and little more, looping around so that its entrances were on the waterfront. At its western end, a lengthy spur was proposed running along the river bed to reach Wallasey, some way to the north.

The map to the right (click to see it full-size) appeared alongside an article in the Liverpool Daily Courier in September 1924. It clearly shows how each branch of the tunnel was to go directly to an existing cross-river ferry terminal.

The route of the tunnel was the least of the Committee's worries. By March 1924, the cost had risen to £7,250,000 and a deputation to Whitehall returned with the news that the government would offer one third of the total cost, on the condition that there were no tolls. The offer was far below what was required and Sir Archibald Salvidge, the leader of the Committee, vowed to fight on.

By September that year, the Road Fund was offering half the £6,500,000 cost, on the basis that it considered anything above this amount to be paying for the tram lines, which the Road Board was not authorised to do. Liverpool said no again and demanded 75% of the cost, not including the tramway provision. It was an uphill struggle, not least because Birkenhead and Wallasey were completely unwilling to offer any funds towards the project.

In March 1925, Birkenhead offered funding on the strict condition that no trams were to be run in the tunnel. Wallasey offered some selfish conditions which were rejected, and so the lengthy (and costly) Wallasey branch was unceremoniously dropped. The scheme proceeded as a Birkenhead and Liverpool joint project. With the trams gone, a suggestion was made that horse traffic use the lower deck.

Eventually — on the pretext of employment relief — the government awarded a grant of 75% of the total costs and work started almost immediately, with the tolls retained and the tramway space built for future use. One has to wonder whether they agreed simply to stop the endless deputations being sent from Merseyside.

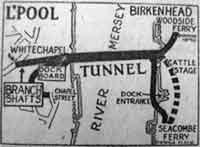

It was only in November 1925 that the configuration of tunnel entrances was fixed — as evidenced by a plan drawn earlier that year (see above and left; click to enlarge), which shows three alternative termini in Birkenhead. The Rendel Street branch was at one point to be the main terminus; and it was only very late in the day that the current main entrance was chosen over the preferred riverfront one.

The following month, Princess Mary Viscountess Lascelles attended George's Dock in Liverpool to formally start work. The Mersey road tunnel was underway.

Going underground

The construction of the tunnel was an incredible feat, involving 1,700 workers. Seventeen of them died in the process. Work was mainly carried out by hand or by small power tools, and it was only after some tentative experiments when the tunnel was already under way that explosives began to be used. Progress was slow and excavation appears to have taken six years, from December 1925 to some time in 1931.

Work progressed from each side of the Mersey, and in 1928 the pilot tunnels met beneath the river. The incredible precision with which the work was carried out meant that the two tunnels were less than an inch off-line. It was a tribute to the skill of the project's engineers — but then the roll-call of civil engineers who worked on the project is essentially a list of great names in British engineering. One of them, Basil Mott, founded the company Mott & Hay, which went on to build the Channel Tunnel, and now in the guise of Mott MacDonald still carries out work on the Queensway Tunnel to this day.

Fitting out the interior of the tunnel — in particular the four-lane road deck suspended across the centre of the bore — took several years more, and it was eventually opened on July 18th 1934 by King George V. The Liverpool Daily Post published an enormous supplement to celebrate the event, including the following pictures and information.

January, 1929: the "mechanical erector" is used to place the cast-iron tunnel lining sections in place. It appears to be a lifting arm that rotates and extends in order to lift a piece of lining and push it into place for fastening. The incredible size of the tunnel and equipment is only clear when you realise there are several tiny people in the foreground and working on top of the machinery.

February, 1931: the full circle of the tunnel, awaiting its road deck, looking from Birkenhead towards Liverpool. It's not clear what the suspended wooden structure at the top is for; it may simply have kept cables and pipes out of the way.

April, 1931. The reinforcing bars are in place ready for the concrete road deck to be poured on this section near to Liverpool. It looks like the tunnel mouth is visible in the distance. In the foreground two sets of temporarily rail tracks are visible, used to move equipment through the site.

June, 1931 and the reinforced road deck has made it into the daylight. Presumably the entrances were the last to be completed as they seal off access to the parts of the tunnel below the road deck. This area is now only accessible through a small hatch.

January, 1931, a lonely worker inspects the concrete somewhere far beneath the Mersey. This the southern side of the lower deck, inside one of two ventilation shafts. The small holes in the ceiling are "airports" — not in the modern sense, of course. They allow air to circulate from the traffic space above into the duct.

The Queensway required everything on a huge, unprecedented scale. The ventilation system — required to evacuate the fumes from very smoky early twentieth century road traffic running underground for long distances — was legendary in scale. This is just one of the enormous fan blades, being erected at John Street in Liverpool.

At Sidney Street, this could be a scene from the film Metropolis, but it's actually two of the enormous fan housings above ground. Again, the sense of scale is provided by two small people to one side.

February, 1932 and the view from inside the tunnel where the exhaust pipe to North John Street ventilation station enters the shaft. The pipe visible above sucks air from the tunnel using the heavy plant in the previous pictures.

The completed tunnel shortly before opening in 1934, with the lofty junction chamber near the Birkenhead end. To the rear, the main bore runs to Liverpool; ahead the tunnel splits with one four-lane branch to Birkenhead and one two-lane branch to Rendel Street. The latter was closed in 1965. Note the direction signs suspended above the roadway and the lack of traffic control.

The main tunnel beneath the Mersey, with elegant lighting embedded in the tunnel walls. (Today the tunnel is lit from an ugly overhead gantry.) The four lanes are marked out quite strangely — the middle two appear to be considerably wider. In the financial year 1939-40, there were 1,925 broken down vehicles rescued from the tunnel, so it made sense to have space to pass stricken vehicles.

The Liverpool ventilation building, seen here in an architectural sketch, stood near to some of the city's architectural treasures (particularly the Liver and Cunard buildings) and so was designed to be something remarkable in its own right.

The Chester Street entrance in Birkenhead. The road layout is very trusting, with nothing to stop vehicles entering through the wrong side of the toll plaza and getting a free journey.

The Old Haymarket entrance in Liverpool, with a slightly different design. Above the tunnel portal is a decorative floor mosaic, and in the foreground the bus station might be a hint at the plans to run scheduled buses through the tunnel. This was strongly opposed by Birkenhead and only happened relatively recently.

One of the "architectural pylons", to the west of the tunnel mouth at Birkenhead. Just behind it is one of the toll booths.

The "central lighting pylon" at the Liverpool tunnel entrance. In the background the familiar shapes of the Liverpool Museum and Art Gallery can be made out. This structure was sadly dismantled in the 1960s, but its counterpart in Birkenhead is still standing.

Liverpool was the second city of the United Kingdom in 1934 and the largest port in the British Empire, and as such was undergoing enormous development. As well as the Queensway Tunnel, it also received the Liverpool to East Lancashire Road, one of the first new inter-city roads built in Britain, which opened in the same year. This (unfortunately faded) image shows its original state, with three unmarked traffic lanes crossing the Lancashire countryside.

Local companies were keen to advertise in the Liverpool Daily Post supplement, and it is sometimes difficult to work out what they are trying to sell you. This one is fairly typical, discussing the tunnel more than whatever company placed it. It proudly proclaims the "world's largest subaqueous tunnel", and opens with the bold statement that "the conquest of the River Mersey is now an accomplished fact", heralding a travel time of 6½ minutes.

The Corporation of Liverpool placed a full-page advert trumpeting the city's merits in language that would be considered unusual today. This extract, with a stylised aerial view of the city, is labelled with "greatest airport in the north", "great £8,000,000 Mersey traffic tunnel", "unlimited supplies of cheap water electricity and gas" and "wide stretches of level country available for immediate industrial development".

Picture credits

- Photographs of construction and opening from a Liverpool Daily Post supplement published 16 July 1934, now believed to be out of copyright.

With thanks to Iain Ellis for information on this page.