In 1965 the Greater London Council was created to fix London's fragmented and uncoordinated local government. And the new GLC was eager to prove its worth with an equally modern solution to London's traffic problem.

The old London County Council was instituted in 1889, its borders reflecting the extent of the Victorian metropolis. But the intervening years saw enormous sprawl into surrounding counties, and by the early 1960s the LCC was an anachronism, its boundaries reaching only to Highgate, Woolwich, Streatham and Hammersmith. Its replacement formally brought parts of Kent, Essex and Surrey into London and wiped Middlesex from the map.

The new Council was responsible for the area we now recognise as Greater London and worked with the 32 new London Boroughs to manage everything from employment and housing to transport, town planning and the Fire Brigade. To demonstrate this new era of coordinated planning, it was also required to set out its vision for the future of London in a single, overarching policy document. It would be called the Greater London Development Plan, or GLDP for short. Writing it would take up the rest of the 1960s.

Going public

The GLC was meant to fix London's planning system, and it had to be fixed to solve what was widely considered an impending traffic crisis. It carried out its duty with some considerable gusto. The first GLC elections, in 1964, produced a Labour majority, with control passing to the Conservatives in 1967 - but while political battles were fought over the work of the Council in many areas, the need for a network of new motorways commanded complete cross-party agreement.

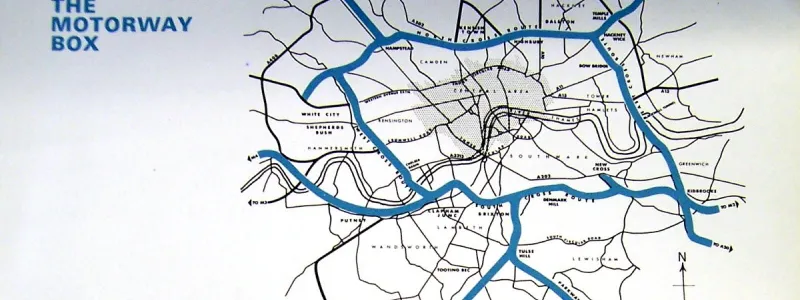

The GLC inherited the LCC's formative motorway plans, which of course only covered the inner part of the new Greater London. It would take planners and engineers some time to extend the plan outwards to cover the whole urban area, but there was no time to waste. Less than twelve hours after the GLC came into being, the outline plan for the London Motorway Box went public.

In 1967, a flurry of publications were issued to explain the motorway proposals. Glossy leaflets with titles like Motorways for London and New Roads in West and North Central London were pushed through letterboxes in affected areas. A 17-page illustrated booklet was published too, called London's Roads: A Programme for Action, with a stirring introduction by the Council's leader, Desmond Plummer. He certainly thought roads were the GLC's main job.

This booklet gives the substance and the background of a decision by the Greater London Council which it is quite safe to say exceeds in the immensity of its scale and the importance of its repercussions any decision ever previously made by a local authority in this country.

At that time, the Primary Road Network - the GLC's term for the urban motorways that would form the backbone of London's new road network - would cost £650m and be completed by 1983. That was, not coincidentally, the year for which the London Traffic Survey made its predictions. A further £110m would be spent on improvements to the Secondary Road Network, those being the existing main roads.

Outside the London Motorway Box, the GLC initially talked about two more ring roads, the "C" Ring and the "D" Ring - echoes of Abercrombie's plans fifteen years after their demise.

Planning a network

Bressey and Abercrombie had sketched lines on maps, but now the GLC was planning in earnest for a decades-long campaign of road construction. The Motorway Box was only the beginning: it now needed a network of motorways to serve the whole metropolis in the same way.

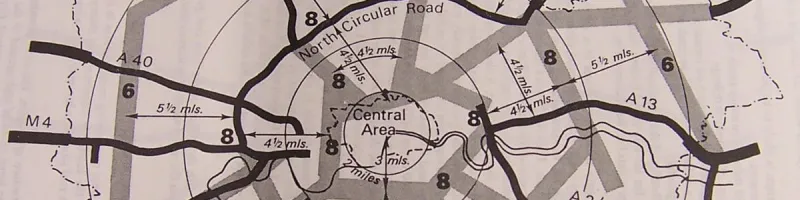

The main purpose of the Primary Road Network, the GLC said, was to serve the suburbs. In Central London, public transport would remain key. Studies of academic research from cities in the US and early results from the London Traffic Survey suggested a ring-and-radial pattern was most suitable for London. A series of "optimum traffic corridors" were identified. London's motorways would attempt to serve those corridors while observing some basic rules. They decided that new roads should:

- avoid "severance" - splitting apart areas that depend on one another

- relate to the structure of the existing road network

- avoid housing demolition, and where it was necessary to run through residential areas, should take property "ripe for renewal"

- minimise the loss of open space

- be placed so that they bounded districts not too small to be useful or too large to be served by the new roads

The realities of trying to fit new roads into London's existing urban fabric meant that the new road network would be twisted and contorted to fit the existing shape of London, a dose of realism that Abercrombie and Bressey had sidestepped. Planners described the difficulty of finding motorway alignments in London, and in most cases had their new roads shadowing railways.

The North Cross Route...lies farther north towards the North Circular Road than its ideal traffic spacing would suggest... Major open spaces, Hampstead Heath and Regent's Park, limit east-west routes to a small corridor which is complicated by the rising land and railway lines in the vicinity of Finchley Road. At the western end the maximum advantage has been taken of a railway location both for the North Cross Route and the M1 extension.

The new network, now being jointly developed with the Ministry of Transport (MOT) as it stretched out into surrounding counties, called for new terminology. The London Motorway Box and Abercrombie's names were out, replaced by Ringway 1, Ringway 2 and Ringway 3. Terse internal memos were dispatched to any Council officer forgetting that "D" Ring was no longer de rigeur, or old-fashioned enough to refer to "Radial Route 7" instead of M12.

Where before there had just been a map of London overlaid with lines representing route ideas, the GLC's planners knew which sections would be completed by 1980 and which were "post-1991". They knew which would require three lanes and which needed four. They could tell you what the junctions would look like and where roads could have a roof added later to create green space on top. They safeguarded alignments against new construction work and decided which buildings would have to be demolished and which would survive. This was no longer a rough outline - it was the detailed blueprint for London's very certain future.

Beyond London's boundaries, the Ministry of Transport had plans of its own. Bressey's proposals for North and South Orbital Roads through the green belt had never gone away and remained in the trunk road programme. That made, in effect, another ring road for London, known as the North and South Orbital Roads - but for simplicity, in these pages, we often refer to it by the unofficial nickname Ringway 4.

At first, the motorways had a respectable level of support, and borough councils were co-operative. It was a rather cosy state of affairs that wouldn't last long.

Opportunity and dissent

The publicity surrounding the motorway plans from 1966 onwards was supposed to create either a sense of excitement at the promising future shape of London, or possibly relief that the city's traffic problems were being addressed. Generally, however, each announcement was met with a mix of horror and dismay by the communities it affected.

The GLC didn't help itself with its choice of terminology. It repeatedly described the spaces it had identified for new roads as "Corridors of Opportunity", a term that couldn't fail to sound callous if your house was within one. One of the most notorious uses of the phrase was at Barnes, where a section of Ringway 2 would have passed through the pleasant and affluent suburb alongside the railway. Few considered the new motorway an opportunity worth taking.

The public were actually still largely in the dark. The motorway plans were frequently debated at County Hall and were the subject of much speculation and anxiety, and yet their routes and construction timetable were maddeningly vague. The debate quickly became national: by 1969, headlines in The Times would simply refer to the "Box" as a familiar shorthand for London's most pressing political issue.

London's local newspapers related a sense of heightening fear and frustration. In 1966, the Evening Standard claimed Ringway 1 alone would cost £3000m and evict 90,000 people. Their numbers were hugely inaccurate, but no official information was available to counter the scaremongering. The tone of this article is typical:

...no further news is known of Ringway 2, apart from that released by the G.L.C. a few weeks ago - which still leaves the exact route undecided, the starting date unknown, and the position of the interlocking traffic exchanges with other motorways still unlocated!

A Ministry spokesman said this week: 'All this is information in the keeping of Greater London Council'.

And it was indeed in the keeping of the GLC, which knew the precise answers but chose not to publish them. A broad plan had been released, glossy leaflets had been distributed, and the details would follow in the GLDP. This strategy was partly about due process - the GLDP would almost certainly go to public inquiry and until that was over nothing was officially decided, so withholding details alleviated planning blight when things might change. But it also meant the GLC was rapidly alienating the people they most needed on their side - Londoners.

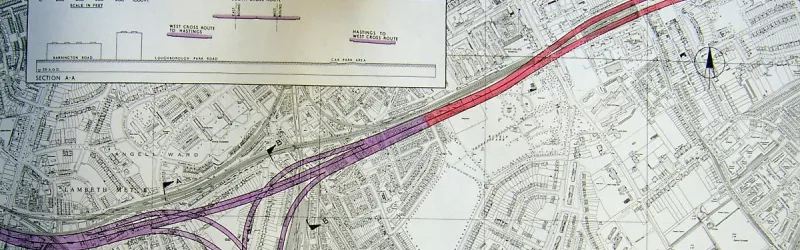

Indeed, during 1969, the GLC repeatedly responded to letters from South London residents by insisting there was "no firm route" for the South Cross Route, a response that was technically and legally accurate but entirely misleading, given that engineering plans for the motorway were produced in 1965. There are records showing that the GLC bought at least two houses on the line of the South Cross Route in Clapham at a total cost of £7,500 because their owners were unable to sell them - a very strange act if, as they claimed, no route had been chosen.

Of course, the people writing to ask about the future of their home were not alone. Concern about a future London ringed and crossed with enormous motorways was widespread as soon as the the outline plan for Ringway 1 was published, and opposition groups were quick to form. By 1967, as work was beginning on the Westway elevated motorway through North Kensington, community groups had already sprung up across London to directly oppose motorway plans in their area.

One lobbying group, the London Amenity and Transport Association (LATA), assembled the resources to commission a report from a group of academics, led by J. Michael Thomson, a research fellow at LSE and an expert in transport economics. It was published in 1969 as a surprisingly readable book, "Motorways in London", that made an impassioned case for a different sort of transport policy. Its pages contained a wealth of academic research that directly countered the GLC's case for the motorway network.

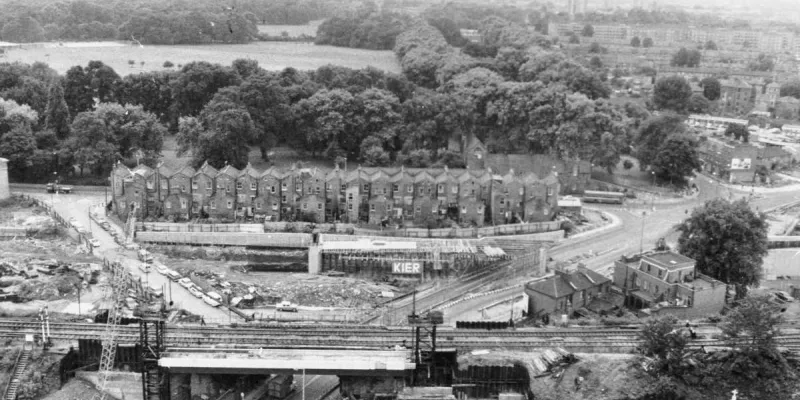

Work couldn't start on the new motorways until the Greater London Development Plan faced a public inquiry and was published - so for now, at least, the growing number of opposition groups had time to make their case. But the GLC was free to get on with things the LCC had already set in motion, which is how the Westway and West Cross Route came to start work in 1967, and how the bulldozers could move in for the East Cross Route and the New Blackwall Tunnel.

Indeed, with two sides of Ringway 1 under construction, you could have been fooled into thinking the GLC's motorways were going to be built. But as well as the growing discontent among the public, trouble was brewing behind the scenes.

A difference of opinion

The GLC had been collaborating with the MOT on urban motorway plans for years, but not all branches of government shared their enthusiasm. In January 1969, a civil servant at the Treasury wrote to the GLC on behalf of Roy Jenkins, then Chancellor of the Exchequer:

The Chancellor would be grateful for a very early note about the plans for a London Motorway Box. In particular he would like to know the route proposed; the cost; the date of construction of the various stages; and what scope there is at this stage for killing the whole project.

Jenkins was trying to balance the books following the devaluation crisis of 1967, and in his Budget speech just a few months later he would raise taxes dramatically to offset the Treasury's spending commitments. Cancelling future capital projects that were expensive and politically difficult would have been a good way to stay in the black, and the GLC's flagship motorway proposal was both colossally expensive and increasingly controversial.

If the memo ruffled the GLC's Highways and Transportation department, the reply sent by Mr Downey didn't show it. He outlined Ringway 1's route, costs and construction dates, and noted that the GLC could only fund it with a 75% Government grant, giving the Treasury a very effective veto. But he optimistically reminded the Chancellor that the Council was "committed" to the scheme.

Jenkins was unmoved, and met with Richard Marsh, then the Minister of Transport, to form a united front. The reply from the Treasury said:

The Chancellor spoke to the Minister of Transport this afternoon about the London Motorway Box, and was glad to find that the Minister shares his own disapproval of the scheme. The Minister will now consider what action should be taken by the Government, and will in due course put a memorandum to Cabinet or a Parliamentary Committee.

The GLC had yet to even publish the GLDP, and already Whitehall was closing ranks. Mostly, it was an issue of cost: inflation was spiralling and within a year of that exchange the price tag for Ringway 1 alone had doubled to an eyewatering £1.7bn. But it was not yet a matter for Jenkins or Marsh to decide upon, and in early 1970 a new Conservative government took office, sweeping aside existing objections for the time being.

Meanwhile, the Greater London Development Plan was finally ready for publication. Before becoming official policy, it had to be reviewed by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government. The minister, Peter Walker, decided that the objections he had received warranted proper scrutiny and so - to nobody's surprise - a public inquiry was convened in July 1970. It would hear all objections, judge each part of the plan on its merits and publish recommendations. The GLC hoped it would not just approve its motorway plans but confirm the urgent need for them, and in doing so bolster the case for Treasury funding.

The notorious GLDP inquiry would last almost two years, making it comfortably the longest planning inquiry in British history until Heathrow Terminal 5 came along in the late 1990s. It was not going to be an easy ride for the GLC.

Picture credits

- GLC coat of arms from Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain.

- GLC publicity as described below.

- Optimum traffic corridor diagram extracted from HLG 159/1024.

- Artist's impression of covered motorway extracted from "Tomorrow's London".

- South Cross Route engineering drawing extracted from the "South Cross Route Consulting Engineers' Interim Report" (1965) in GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/097.

- Archive photograph of East Cross Route under construction is used under licence from London Metropolitan Archives, City of London (Collage record number 247124).

- Photograph of Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead by Walter Bird, 17 December 1963 (NPG x166847) © National Portrait Gallery, London used under this Creative Commons licence.

Sources

- Creation of the GLC; requirement for GLDP; purpose to fix planning system: Hart, Douglas (1976). "Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network". London: Pergamon.

- Publications explaining motorway network: "New Roads in West and North Central London", extracted from MT 106/437; "Motorways for London", extracted from GLC/DG/PUB/01/380.

- Desmond Plummer on the motorway network; cost £650m; completion by 1983: "London's Roads: A Programme for Action" (1967). London: Greater London Council.

- Optimum traffic corridors and principles of planning urban motorways: HLG 159/1024.

- "The Box" as shorthand for motorway proposals: "Labour thoughts on the Box", The Times Diary, The Times, 7 February 1969.

- "Corridors of Opportunity": Buchanan, CM (1970). "London Road Plans, 1900-1970". London: Greater London Council.

- Inaccurate figures in the press: "That motorway box 'could cost £3000m'", Evening Standard, 26 May 1966.

- GLC inform residents there is "no firm route" for South Cross Route; purchase of houses in Clapham: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/069.

- LATA purpose and arguments against GLC/PRN: Thomson, JM (1969). "Motorways in London; report of a working party, led by J. Michael Thomson". London: Gerald Duckworth & Co.

- Correspondence between Treasury and GLC about "killing the whole project"; cost estimate at £1.7bn in 1970: T 319/1842.