This was the most desperately-needed of London's new motorways, if the GLC were to be believed, intercepting and dispersing heavy traffic loads approaching the central area from the west.

Special plans were made to get it built as soon as was possible, and it is one of the only motorway plans that were ever progressed to the construction stage. A tiny fragment of road was built and is still there to be driven today. It doesn't live up to the grand name West Cross Route, but it was even less suited to its old motorway number, M41.

This part of Ringway 1 follows the route of the West London Line railway very closely, and it would have been elevated for most of its length from Harlesden to Wandsworth.

It was originally planned to have four lanes on each carriageway. However, the full width was only justified if it formed part of Ringway 1, and it was thought to be so urgently needed as a bypass to local roads that it was proposed to build it as a dual two-lane elevated motorway, with provision to widen it to the full dual-four lane configuration later on, when the full Greater London Development Plan, including the rest of Ringway 1, had cleared public inquiry.

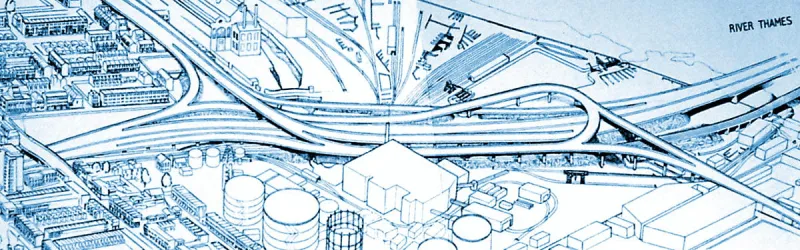

Two studies were conducted into its alignment, both by consulting engineers Husband & Co. Every detail of the road, from its alignment and elevation to its junction layouts, was planned at this stage and it was even known where each supporting pillar would be placed in relation to the railway tracks beneath it. Further revisions were made in 1970, again with no shortage of plans and diagrams. That - and the fact that a section of it actually exists - means we have a very clear picture of what this road was supposed to look like.

Outline itinerary

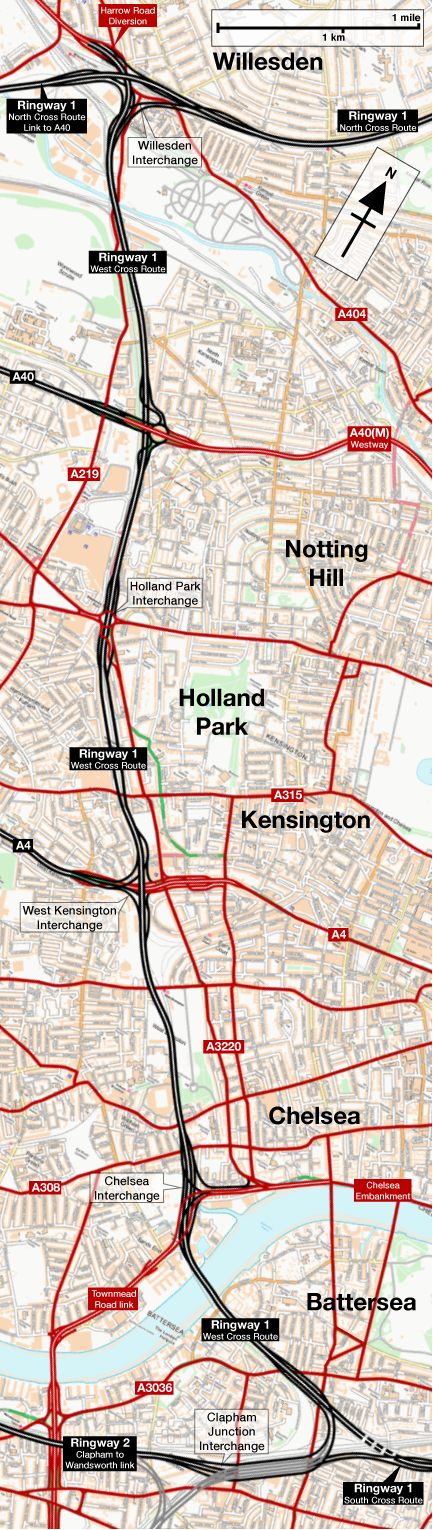

Continues to North Cross Route

Links towards A40 and Harlesden (Willesden Interchange)

A40 and A40(M) Westway (Interchange)

Shepherd's Bush (Holland Park Interchange)

A4 (West Kensington Interchange)

Chelsea Embankment Spur and link to Townsend Road (Chelsea Interchange)

Bridge over Thames

Clapham-Wandsworth Link (Clapham Junction Interchange)

Continues to South Cross Route

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £48,030,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £71,315,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £4,053,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £123,398,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£2,046,971,262 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

Route map

Scroll this map to see the whole route

Scroll this map vertically to see the whole route

Route description

This description begins at the southern end of the route and travels north.

Clapham to West Kensington

Continuing from the South Cross Route, Ringway 1 would have interchanged with the Clapham-Wandsworth Link in the vicinity of Latchmere Road, threading the sliproads of a triangular three-way motorway interchange under and around the complex tangle of railway tracks, emerging from an underpass below the Victoria and Waterloo lines to run along the north side of the West London Line railway.

Crossing the Thames on a new bridge, there would have been a large free-flowing interchange with the "Chelsea Embankment Connection", a spur motorway linking to the Chelsea Embankment itself. The embankment and the road onwards all the way to Westminster were supposed to be turned into a riverside dual carriageway - indeed parts of it were, and still are today - and hazy plans existed at the time to build a futuristic new tunnel bypassing the Houses of Parliament so the road could flow directly into the Victoria Embankment towards the City.

The complex interchange at Chelsea would have been adjacent to the former Lots Road Power Station and was to be almost entirely elevated above ground level. Its looping sliproads would permit full access between Ringway 1 and the Embankment spur, and access to and from the north for another spur linking to Townmead Road. A vastly upgraded Townm Road would have formed a free-flowing dual carriageway route on to Wandsworth Bridge.

Continuing north from the Chelsea Interchange, the motorway would have run on a viaduct directly above the railway line, rising up even higher at certain points to clear existing road bridges across the tracks. A short double-bend would take the motorway directly behind what was then Earl's Court Exhibition Centre. In 1991 an extension to the building, Earl's Court Two, was built spanning the railway and blocking any chance of building the motorway or anything like it, and in recent years Earl's Court itself has been replaced with a new high-rise housing development.

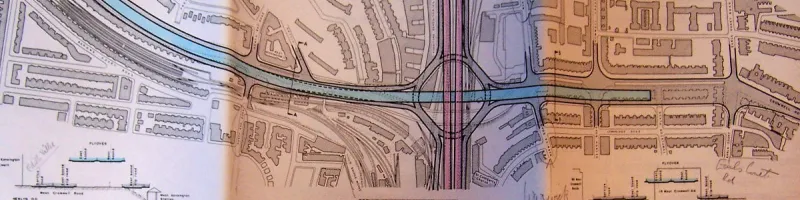

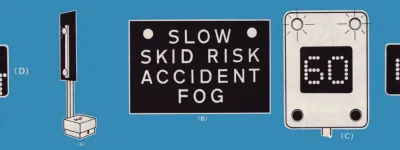

Still running directly on top of the railway, the motorway would then reach an interchange with the A4 at West Kensington. Two different designs were proposed here. Early designs show a three-level stacked roundabout, with several alternatives drawn up. One concept was an enormous saddle-shaped roundabout draped across the motorway, while another had a smaller, diamond shaped roundabout. Later designs showed a free-flowing interchange that would serve only the A4 to the west, with no access to or from Central London.

West Kensington to Harlesden

North of the A4, the road would have continued along the West London Line, with the carriageways splitting apart to run either side of Olympia station. This odd arrangement, with the West London Line in the middle of the elevated motorway, would then continue almost until Holland Park Roundabout. Initial proposals for an underpass here were rejected because of the steepness of the resulting slope between the underpass and elevated viaduct. A flyover was proposed there instead. Sliproads to and from the south would connect with Holland Road before joining the roundabout.

The large diamond-shaped Holland Park Roundabout was actually built, ready to receive its flyover, and from that point northwards to the A40 the West Cross Route was actually built, opening in 1970 with the number M41.

The roundabout is surrounded by low concrete walls which, in some places, do not quite match the current layout of the road, giving away the original intention for the junction. At the south-west corner of the junction, one drifts oddly away from the road towards the railway, following what was supposed to be the edge of the northbound off-slip from the motorway as it joined the roundabout. It then actually strikes out over the railway line, a strange stub of elevated road that now carries only grass and a concrete wall to stop urban explorers dropping onto the tracks below.

The extant part of the motorway was designed at an earlier stage than the rest of the West Cross Route and was built to a less ambitious standard, with three lanes and a hard shoulder in each direction, a standard that seemed adequate when it was planned in the very early 1960s, but which would have been narrower than the sections to the north and south if they had been completed. It might well have been widened if the rest of the route had been built.

In the late 1990s the short section of road lost its motorway status and was extensively reconstructed, and it is now a dual two-lane road without hard shoulders. A new intermediate junction has been built, with its sliproads entirely constructed within the original width of the road. The best guide to its original width is immediately north of the Holland Park Roundabout where there is an awful lot of spare tarmac and white paint.

At the northern end of this short section, the motorway would pass underneath the A40(M) Westway (now simply A40) just west of the elevated roundabout. The twisting, elevated structures that now carry the West Cross Route up to the roundabout were supposed to be sliproads leading off either side of the motorway.

North of the Westway, the West Cross Route would have swept across yet more of North Kensington, following the east side of the railway. The terraces of Victorian houses actually have stubs of sliproads pointing menacingly at them from the Westway roundabout, a concrete statement of intent that was never fulfilled. Most of the northern half of Latimer Road, already sliced in two by the Westway, would have disappeared.

On reaching Willesden Junction, a windswept complex of railway tracks and sidings amid scrubland and low-rent industrial land, a large and complicated free-flowing interchange would have completed the circuit around Central London by connecting the motorway to the North Cross Route. Access would also be provided west towards the A40 and north to the A404 Harrow Road.

Full circle

The motorway route described above, forming the western side of Ringway 1, would have been far more important than the shorter motorway route it would cross at White City, the A40(M) Westway. Oddly, the earliest ancestor of the West Cross Route was as a short spur to the Westway, in which role it would have been much less important than its parent.

In 1959, the A40 Western Avenue terminated at Wood Lane, and all traffic approaching London from the west on this grand approach road had to stop, turn right and travel down the street to Shepherd's Bush Green where it could join the old Uxbridge Road towards London. Plans were drawn up for a new elevated route alongside the Underground to connect the end of Western Avenue to Marylebone Road - the route we now know as Westway.

In its earliest guise, the planners of the 1950s intended their new road to have a spur from a trumpet interchange at White City to Holland Park, bypassing Wood Lane, along precisely the line of the West Cross Route proposal. What is now the Holland Park Roundabout would have been a signal-controlled crossroads.

It's not hard to imagine that, in the years that followed, planners at the LCC looking for a suitable route for a new motorway flanking the west side of London saw that spur in their plans and realised it could be continued in the same fashion alongside the railway both north and south, creating the West Cross Route plan detailed here.

By the time the Westway was being built, the whole West Cross Route was in planning. The scheme included construction of a short section of the new motorway from White City to Holland Park, all designed with space for flyovers and underpasses to continue it north and south. Ironically, that short section is the only part of the West Cross Route that was ever built, and it has only ever served the function of the short spur that was originally envisaged.

The open road

The section between the Holland Park Roundabout and A40(M) Westway opened in 1970. At its northern end it joins Westway at an elevated roundabout that was obviously built with provision for the northern part of the West Cross Route to plug in. The roundabout makes frequent appearances in traffic reports as the "Northern Roundabout", though this was never its official title - it's simply the northern roundabout of the West Cross Route as built, and by some misunderstanding that has come to be its name.

The existing road is well known by both its title, West Cross Route, and by its former number, M41, which was the most absurdly pompous designation considering that it was just a mile or so of dual carriageway between two roundabouts.

One might expect its number to be an indication of the number intended for the whole of the West Cross Route or perhaps the whole of Ringway 1, but M41 seems profoundly unlikely to be it, given that we know at least part of Ringway 2 was allocated the number M15 and Ringway 3 was M16. Correspondence within the Ministry of Transport from 1972 about motorway numbering in the West Midlands reveals that the number M41 "became attached to the West Cross Route at an early stage", and the actual allotted number was meant to be M14. That fits the pattern of other numbers much better. Perhaps the digits were accidentally transposed, or "14" was assumed to be a mistake by some well-meaning soul who thought "41" was a better fit for a road that would initially be a short spur from the A40.

The West Cross Route, as built, remains an outstanding example of why building one isolated fragment of a motorway project is rarely a good idea. The West Cross Route today dumps all its traffic onto the urban roads of Shepherd's Bush and Kensington, and since 1970 has been failing to make a convincing job of relieving any urban streets of heavy traffic at all.

That's not to say the whole West Cross Route would have been a folly - an extension of the motorway as far as the A4 would have been genuinely useful and meant that highly unsuitable residential streets would not be used as a de facto dual carriageway around West London, as they are now - but the plug was pulled in the very widespread shock and disgust surrounding the completed Westway, and the one tiny section that now exists could never hope to do much on its own.

Half a motorway

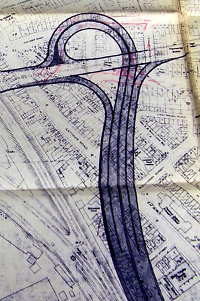

The consulting engineers Husband and Co. produced reports on the design and construction of the West Cross Route in 1962 and 1964, but a major revision of the plans was carried out in 1970, at which time the proposal became quite different.

In the mid-1960s a dual three-lane motorway was proposed, and that's the standard the short extant section was originally built to, but dual four-lanes with hard shoulders on both sides were thought to be the ultimate requirement. Concerned that the traffic situation west of Central London was particularly bad, the GLC intended the West Cross Route to begin construction as early as possible, but if it preceded all the other motorways it would eventually connect to, a design was needed that would work as an interim stage.

The resulting plans are astonishing. The engineers drew up designs for half a motorway: two lanes and a hard shoulder each way on an elevated structure that would ultimately form half of the total width. In its smaller guise, the road would be quicker and cheaper to build and could begin providing relief to Kensington and Chelsea much sooner, and being designed to have the other half bolted on later meant that doubling its width would be no problem.

The new 1970 designs also included revised layouts for the junctions at the A4 and the Chelsea Basin. A free-flowing junction with no access to or from Central London was devised for the A4, while the Chelsea Basin's new layout allowed it to form a temporary terminus for the motorway until it could be extended south over the Thames to the South Cross Route.

The GLC began the legal and administrative processes to start construction on the West Cross Route, and in 1970 it expected that Phase I works would begin on site in 1972. The GLDP Inquiry caused the start of work to be postponed, much to the GLC's irritation, until 1973 local elections when the incoming Labour administration cancelled it and every other motorway plan.

Back from the dead

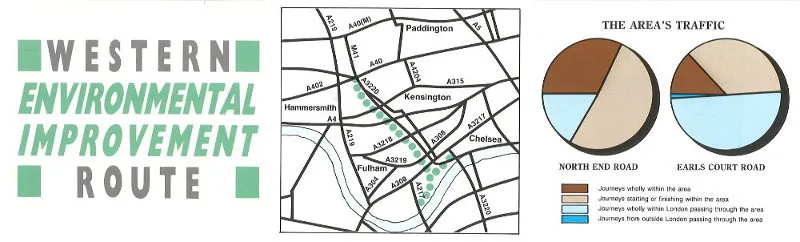

After the Ringway plan was cancelled, the idea of the West Cross Route refused to disappear with the other motorway plans. Traffic in Kensington continued to be appalling - it still is - and the Earl's Court one-way system continued to be a major problem for traffic flow and residents alike.

Something like the West Cross Route, on a smaller scale to serve the role of bypassing the local streets without it being part of a wider motorway network, seems to have stayed in the back of planners' minds for a long time after the motorway was called off. For example, at the time the M1 was extended south to its current terminus at the North Circular Road in 1979, space was left for the southward continuation of the motorway, long after London's motorway plans were dead. It seems to have been done to allow for the very distant hope that an extension could be built along the proposed line of Ringway 1 to meet the West Cross Route.

In 1986 the GLC was disbanded, and responsibility for the major roads it had managed passed to the Department of Transport who maintained them as trunk roads. A pro-motoring Conservative Government took over London's roads from a decidedly left-wing Council and immediately started looking at ways to ease traffic flow. A study was commissioned, carried out by civil engineers Halcrow, to recommend ways to resolve the serious problems in west and south-west London.

In 1988, the DTp accepted Halcrow's recommendations and published plans for one of the new roads they had proposed, the Western Environmental Improvement Route or WEIR. It was the West Cross Route, exhumed and presented in smaller form, and indeed the original engineers, Husband and Co., were involved in the design once again.

A partly grade-separated dual carriageway would have run alongside the railway from Holland Park Roundabout to Chelsea Basin, forking into two single-carriageway branches at its southern end to split cross-river traffic between Battersea and Wandsworth Bridges.

A consultation was carried out among the residents of Kensington and Earl's Court, but the promises of a traffic-free Earl's Court and a pedestrianised North End Road didn't seem to find favour. Within a year or two the Government had backed down and the West Cross Route finally vanished down the plughole never to be seen again. The space does not now exist for such a road to be built.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Artist's impression of Chelsea Interchange, plan of roundabout junction with A4: "West Cross Route south of Holland Park Avenue: Consulting Engineers' Report", London County Council, April 1964, extracted from MT 106/188.

- Archive photographs of West Cross Route under construction are used under licence from London Metropolitan Archives, City of London (Collage record numbers 248615 and 248578).

- Plan of trumpet interchange extracted from MT 106/93.

- Plans of Holland Park Interchange and free-flowing junction with A4: "West Cross Route Holland Park Avenue to Chelsea Basin Engineering Report Vol. 2", Greater London Council, May 1970, extracted from GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/098.

- WEIR consultation leaflet published by the Department of Transport, 1988, and used under the Open Government Licence.

Sources

- Route, Clapham Junction to Holland Park: MT 106/188, West Cross Route: Interim Report on Stage I (1962)

- Route, Holland Park to Westway: this road already exists; T 319/1842 confirms the whole route.

- Route, Westway to Willesden Junction: MT 106/437

- 1964 proposals, including Chelsea Interchange and A4: MT 106/188

- 1970 proposals, including revised interchanges and plan to initially only build half the structure: GLC/TD/DP/LDS/02/098

- Western Environmental Improvement Route: leaflet published by the Department of Transport, 1988, reproduced in full above; "West London Assessment Study, Stage II", Halcrow and Partners, 1988.

- Proposal to link Chelsea and Victoria Embankments: Document Supply 85/31736

The original text on the West Cross Route, from which this page has been adapted, was written by Tom Sutch.