Of the four rings planned around London, Ringway 3 was the one that almost everybody could agree on. Even the two main protest groups, fiercely opposed to urban motorway building, supported Ringway 3. So why was only half of it ever built?

Ringway 3 was designed to be an orbital motorway positioned about twelve miles from the centre of London, with the purpose of carrying long-distance traffic around the edge of the city so that it wouldn't pass through. That would appear to be the job of the outermost ring, and indeed the Greater London Council invariably described Ringway 3 as the third and final ring road forming the outer periphery of the city's road network. But even as they were saying it, the Ministry of Transport were gearing up to build a fourth ring further out.

This was, like so many of the individual projects that made up the Ringways, descended from one of Abercrombie's proposals. His system of five ring roads were known by letter, and his "D" Ring later became Ringway 3. In consequence, some parts of the motorway would occupy space set aside for the modest sort of highway envisaged by 1940s town planners. The motorway would swallow up the brand new Dartford Tunnel (opened in 1963) and some scattered bits of "D" Ring Road in Middlesex that had already been built just after the war.

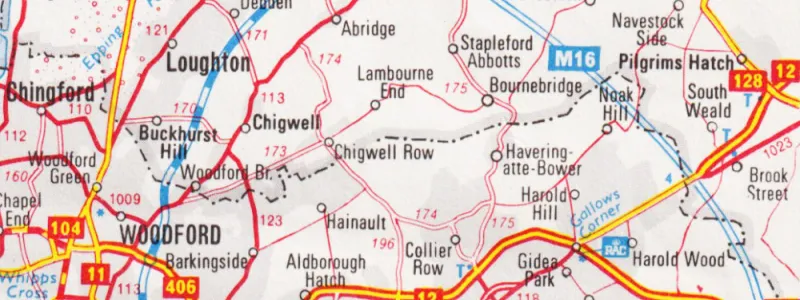

The plan was, in comparison to Ringways 1 and 2, pleasingly simple. This motorway stayed out of densely-populated inner London, and in many places ran through uncontroversial open space. Responsibility for the whole circuit was with the Ministry of Transport, keeping it clear of the relatively excitable GLC. And in October 1966, the London Highways division of the Ministry made a decision that the complete ring would be a motorway, allocating it the number M16.

As public opposition to London's urban motorways grew, the London Motorway Action Group (LMAG) and the London Amenity and Transport Association (LATA) both agreed that Ringway 3 should still be built, approving of an outer ring road to keep through traffic away from the city. But not all of Ringway 3 would be as straightforward as it first seemed.

It turned out to be a ring of two distinct halves. In the north and east, it ran almost entirely through open country, and progress was easy. Parts began to open to traffic from 1975 onwards. In the south and west, though, a distance of 10-14 miles from the centre put the motorway through plenty of well-established suburbia. In north west London, no agreement could be reached on where the road should go, and every government body with a stake in the road put forward their own suggestion. It's now virtually impossible to keep track of all the competing ideas. In the south, no line was even selected before the project was dropped.

1973 saw the cancellation of all the GLC's motorway plans, and the publication of the Layfield Report, which called for a single outer ring motorway. The idea was to build one ring from whichever components of Ringways 3 and 4 were easiest, with some minimal new road to link them up. Ringway 4's South Orbital Road was pretty much ready to go at that time, which avoided the need to battle through intractable problems in south and west London. It was connected to the north and east sides of Ringway 3, which were making steady progress towards completion already, to form the "London Outer Orbital Road". We now know this patchwork road by a different name. It's the M25.

What follows, then, is a history in two parts. The north and east sides of Ringway 3 will be familiar, tracing the history and the route of about half of the modern M25, though that doesn't mean there's nothing new to discover. The south and west sides are something else entirely: a tour of a whole range of urban motorway proposals, remarkably destructive and fearsomely difficult to build, and a story of long-running battles between government departments over where exactly London's third ring road should go - and even, at times, what it was for.

Picture credits

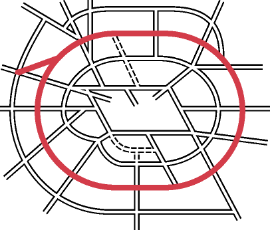

- Interchange plan extracted from MT 106/287.

- Extract of map showing M16 is from RAC England & Wales (1977), produced for the Royal Automobile Club by George Philip Group.

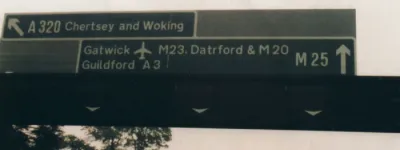

- Photograph of Bell Common Tunnel is from Department of Transport (1986). The M25 Orbital Motorway.

Sources

- LATA and LMAG supported construction of R3: Hart, D. (1976). Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network. London: Pergamon, p168.

- R3 located 10-14 miles from central London: HLG 159/1024.

- GLC describe R3 as outermost; purpose to serve long distance traffic: good example in (1969). This way to London: A summary of the Greater London Development Plan. London: GLC.

- R3 adapted from Abercrombie's "D" Ring: Buchanan, C. (1970). London road plans, 1900-1970. London: GLC, p45.

- Responsibility entirely with MOT; designated motorway Oct 1966: MT 106/413.

- Adapting advanced parts of R3 and R4 to form one ring: HLG 159/626.

- London Outer Orbital Road name: MT 120/314/1.